A couple of months after Donald Trump won the 2024 election and right after he had nominated conspiracy-mongering antivax activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. to be Secretary of Health and Human Services, I wrote a post entitled RFK Jr. vs. the NIH: Say goodbye to the greatest engine of biomedical research ever created. I admitted at the time that the title might seem a bit overwrought, but I wanted to drive home the problem of putting RFK Jr. in charge of HHS, under whose purview the National Institutes of Health lie. At the time, even I thought I might have been exaggerating a bit, but something happened on Friday that makes me think that, if anything, I might have been a bit too mild, even after a couple of weeks ago, when Trump’s minions started canceling NIH study section meetings and putting a temporary pause on travel by NIH employees, even to scientific meetings to present their science. This all happened happened before RFK Jr. has even been confirmed. It’s even before Trump’s awful nominee for NIH Director, the COVID-19 minimizing antivax-adjacent, conspiracy mongering Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who’s also the co-author of the Great Barrington Declaration, the social Darwinist COVID-19 manifesto to “let ‘er rip” to reach “natural herd immunity” (with poorly defined “focused protection” to protect the elderly and vulnerable), has started confirmation hearings. Friday night, it got even worse.

Here we go.

Elon Musk and DOGE slash “indirect costs” (more formally F&A)

One of the gratifying things about writing for this blog is the ability to explain how seemingly esoteric policies can affect medical research and science-based medicine. For example, before Friday it certainly wasn’t on my bingo card to write about indirect costs awarded to universities with NIH research grants, but leave it to Elon Musk and his “department of government efficiency” (DOGE, which isn’t a real department, hence my refusal to capitalize its name) to unilaterally and without warning slash indirect costs associated with NIH research grants. I’ll explain what indirect costs are in a moment. For now, just understand that indirect costs go to the university to support the general infrastructure necessary to carry out NIH-funded research, including grant administration. First, however, here’s the announcement, going under the seemingly boring title Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates (Notice NOT-OD-25-068). Behind that seemingly innocuous title lays potential devastation for medical schools and universities receiving NIH grants to do biomedical research under the guise of “providing indirect cost rates that comport with market rates.” First, here’s the policy:

For any new grant issued, and for all existing grants to IHEs retroactive to the date of issuance of this Supplemental Guidance, award recipients are subject to a 15 percent indirect cost rate. This rate will allow grant recipients a reasonable and realistic recovery of indirect costs while helping NIH ensure that grant funds are, to the maximum extent possible, spent on furthering its mission. This policy shall be applied to all current grants for go forward expenses from February 10, 2025 forward as well as for all new grants issued. We will not be applying this cap retroactively back to the initial date of issuance of current grants to IHEs, although we believe we would have the authority to do so under 45 CFR 75.414(c).

Again, bear with me a moment. I will explain what indirect costs are. Just note that most universities have negotiated indirect cost rates between around 40-70%; so this is an immediate and unannounced cut. The rationale used? Whoever wrote this announcement pointed to indirect rates offered by private foundations that offer research grants, which max out at around 15% and then claim that they’re being generous by “only” cutting indirects to 15%. The NIH even posted this to X, the hellsite formerly known as Twitter, justifying its cuts:

With Elon Musk himself proclaiming:

So, are indirects the “ripoff” that Musk claims? I can tell right there that “siphoning” off is a misunderstanding, whether intentional or disingenuous, meant to make it sound as though universities are taking up to 60% off the top for themselves. In reality, indirects are in addition to the direct costs of the grant. If you have an indirect rate of 60%, that means that if your university is awarded an NIH grant for $1M, the university actually gets $1.6M. That means that, of the total grant, a 60% indirect cost rate is really only 37.5%. (See Musk’s deception there?)

Basically, this is the justification in the announcement:

Indeed, one recent analysis examined what level of indirect expenses research institutions were willing to accept from funders of research. Of 72 universities in the sample, 67 universities were willing to accept research grants that had 0% indirect cost coverage. One university (Harvard University) required 15% indirect cost coverage, while a second (California Institute of Technology) required 20% indirect cost coverage. Only three universities in the sample refused to accept indirect cost rates lower than their federal indirect rate. These universities were the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Michigan, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The United States should have the best medical research in the world. It is accordingly vital to ensure that as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead. NIH is accordingly imposing a standard indirect cost rate on all grants of 15% pursuant to its 45 C.F.R. 75.414(c) authority. We note in doing so that this rate is 50% higher than the 10% de minimis indirect cost rate provided in 45 C.F.R. 75.414(f) for NIH grants. We have elected to impose a higher standard indirect cost rate to reflect, among other things, both (1) the private sector indirect cost rates noted above, and (2) the de minimis cost rate of 15% in 2 C.F.R. 200.414(f) used for IHEs and nonprofits receiving grants from other agencies.

This is next level ignorance. The reason why most universities are willing to accept lower indirect cost rates is because private grants like the ones from foundations listed in the announcement (e.g., the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation) is because most universities know that foundation grants are often stepping-stones for younger investigators to obtaining larger and more prestigious grants, especially from the NIH. Basically, universities don’t like the lower rates, but accept them in order to help nurture younger investigators.

Also:

Many who advocate for cutting NIH’s indirect cost rate have long argued that universities are willing to accept lower rates from philanthropic foundations. Today’s NIH notice, for example, notes the Gates Foundation limits indirect costs to 10%, while the Packard Foundation sets the ceiling at 15%. But such reasoning is based on “perverse logic,” Corey says, because foundations use their funds to increase the productivity of research infrastructure already paid for by the federal government. And universities say they are often willing to accept foundation grants that carry low overhead rates because those grants amount to a relatively small fraction of their funding. Another key reason that indirects seem to be lower for foundation grants is that foundation grant mechanisms tend to be more flexible in terms of what they allow investigators to budget for in the direct costs, meaning that some of what is covered by federal government indirects can be included in the direct costs budget for a foundation grant.

Going back to 2017 again:

University officials, however, say comparing NIH and foundation overhead rates is misleading. Gates, for example, is more expansive than NIH in defining direct costs, meaning some overhead payments are wrapped in with the grant. The Trump proposal “does not reflect [the foundation’s] process for determining direct or indirect costs,” a Gates spokesperson says. Universities note that they are often willing to accept foundation grants that carry low- or zero-overhead rates because those grants amount to a relatively small fraction of their funding—something they could not afford to do for major funders.

Everything old is new again.

Before I describe what indirect costs are and how they are calculated and awarded, I would be the first to state that there has long been a widespread recognition that indirects have gotten out of hand at some universities, with some having argued that they need to be reined in, preferably to make more dollars available to distribute to more researchers in the form of NIH grants, particularly given how low the paylines have gotten (less than 10 percent of grant applications funded). There’s definitely a policy discussion to be had there, but such a discussion would have to include a sober, evidence-based consideration of the trade-offs involved in shifting money from indirects to more grants that would take months, if not years, and be phased in gradually so that universities and investigators would have time to adapt. Instead, what we got was a hastily issued Friday night announcement that is causing massive confusion and consternation at every university and research institute that receives NIH grant funds. I never thought I’d see news reports like these about indirect costs, which are, again, an esoteric topic that few people outside of universities, academic medical centers, research institutes, and policy wonks know about, but here we are:

Let’s go back to 2017, when the first Trump administration tried to slash indirects:

The federal government has been adding indirect cost payments to research grants since 1947. Today, each university negotiates its own overhead rate—including one rate for facilities and one for administration—with the government every few years. Rates vary widely because of geography—costs are higher in urban areas—and because research expenses differ. Biomedical science, for example, often requires animal facilities, ethics review boards, and pricey equipment that aren’t needed for social science. The base rate for NIH grants averages about 52%—meaning the agency pays a school $52,000 to cover overhead costs on a $100,000 research grant (making overhead costs about one-third of the grant total). Universities usually don’t receive the entire 52%, however, in part because some awards for training and conferences carry a lower rate, and because certain expenses such as graduate student tuition don’t qualify.

At the time, political opposition scuttled this proposal.

Again, it is not unreasonable to argue that indirect cost rates have gotten too high; what is unreasonable is to think that suddenly slashing them without warning, including on existing grants, won’t cause devastating harm to universities.

Indirect costs (also called F&A): What are they and why are they so high?

Thus far, I have only given the broadest and simplest description of what “indirect” costs are for NIH grants. It’s now necessary to discuss them in more detail.

Here we have to get into a little “inside baseball” talk with respect to the NIH, much as I’ve done before when discussing, for instance, NIH study sections and how research grants are evaluated, ranked, and ultimately chosen (or rejected) for funding. NIH grants are divided into two parts. The first is direct costs, which include salaries, supplies, and other expenses associated directly with doing the research proposed in the grants. The second part is what is known as indirect costs, or, more formally, Facilties and Administration (F&A). This is money that is provided to the university receiving the grant, in addition to direct costs, to help cover costs involved with the research, such as building maintenance, office space, support staff, grant administration, clinical trials administration, generally used equipment, and the like. While often portrayed as a “slush fund” (and, yes, occasionally some universities have abused F&A, in reality they are used as portrayed, as described here:

And:

From the last time the Trump administration tried to slash F&A costs, here’s a video:

It is, of course, a reasonable question to ask why universities aren’t paying for these things themselves. To a significant extent, they are. Ask any dean of a medical school, and they’ll tell you that research is usually money-loser, not a profit center, because the infrastructure to do research that can compete to win NIH funding is very expensive. From 2017 again:

Critics of the proposal predict that richer, private institutions, which often have endowment income and fundraising prospects, would have an easier time coping with lower overhead payments. But research facilities at some state universities “would just become derelict,” predicts Mary Lidstrom, vice provost for research at the University of Washington in Seattle. “We would have to pick and choose what small number of grants we could support.”

But why are indirect costs formally called “F&A” (Facilities & Administration)? Let Michael Nietzel, a former college president, explain:

Indirect costs involve a myriad of necessary overhead expenses that universities take on when they conduct research. They are typically divided into two categories – “facilities” and “administration” — and include items like maintenance of equipment, facility upgrades, the operation of labs, depreciation, employment of support staff, accounting, research compliance, legal expenses, and the salaries of key administrators in charge of an institution’s research enterprise.

Universities depend on indirect cost reimbursement to defray a significant portion of these expenses, and a cut of this magnitude will leave many of them scrambling to fill the huge budget holes that it almost immediately creates.

Again, no one—and I mean no one—is claiming that indirects/F&A are sacrosanct and should be immune from discussion and potential decreases in rates. Lots of academics, scientists, and those involved with biomedical research have been arguing that, for some institutions at least, they’ve gotten too high. Indeed, periodically there have been efforts to rein them in, for example (again) in 2017:

Many universities have long complained that their negotiated rates don’t cover true research costs. Congress and federal officials, for their part, have repeatedly tried to rein in overhead payments. Most notably, in 1994 officials capped the administration rate for universities at 26% after Congress became concerned that schools were misusing the money. But for decades the share of grants from funding agencies devoted to indirect costs has remained fairly steady.

Note again, that Musk intentionally cherry picked institutions with the highest F&A rates negotiated with the government. (Incredible, I know.) Also:

President Barack Obama’s administration also floated setting an unspecified flat rate, which economists said would increase efficiency and reduce paperwork.

This brings up an important point. F&A rates are negotiated individually, university by university. Moreover, notice how DOGE and MUSK have targeted universities that have negotiated the very highest F&A rates. For most universities, the rate is a lot lower. Rates are affected by location and expenses that vary by location (e.g., large urban areas versus rural locations), as well as the sophistication of the infrastructure at each university. Even more interestingly, it is not the NIH that negotiates these rates with universities, as explained here:

F&A costs are determined by applying your organization’s negotiated F&A rate to your direct cost base. Most educational, hospital, or non-profit organizations have negotiated their rates with other Federal (cognizant) agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services or the Office of Naval Research. If you are a for-profit organization, the F&A costs are negotiated by the Division of Cost Allocation (DCA), Division of Financial Advisory Services (DFAS) in the Office of Acquisition Management and Policy, NIH.

Here’s why:

F&A cost rates for colleges, universities, nonprofits, hospitals, and state and local governments are established by the HHS Division of Cost Allocation or the Department of Defense’s Office of Naval Research. Once a federally-funded rate is negotiated and established, it applies to all government funding agencies that support your grantee institution.

NIH sets F&A cost rates only when the grantee is a commercial organization (e.g., small businesses). In these cases, the Division of Financial Advisory Services in NIH’s Office of Acquisition Management and Policy will set the rate for the grantee organization.

If a grantee institution does not have a negotiated rate at the time of its award and it does not wish to pursue negotiations to establish one, it can elect to receive a “de minimus” rate, which is 10 percent of Modified Total Direct Cost (MTDC).

And:

NIH research funding supports both direct and F&A costs associated with research. But non-research and research activities costs must stay separated since NIH applies the F&A cost rate on the F&A costs associated with research activities only.

Additionally, facilities costs are limited to the spaces that are used only for research. Separating direct and indirect costs helps ensure that the reimbursements issued on NIH grants solely support the conduct of research.

The American Association of Medical Colleges provides a useful infographic:

All of the above is why, for instance, the indirect cost rate for a federal research grant to researchers at a university will be the same, regardless of whether the grant is funded by the NIH, National Science Foundation, or, for example, the Department of Defense. (Yes, the DoD funds medical research. I myself have had DoD grants in the past, which makes me wonder how long it will be before DOGE realizes that indirects are paid on top of research grant direct costs by more federal agencies than just the NIH.) Also note that non-research grants (such as fellowship or training grants) do not provide F&A costs, and that there are a lot of limitations on what expenses F&A can be used to cover.

But why? Why did the government start paying indirect costs associated with NIH grants in the first place? Yale scientist Dick Aslin provides the historical explanation, even asking whether we’re paying too much for biomedical research, explaining why the nation’s research effort is distributed among our universities, rather than in research institutes set up by the government, not just for biomedical research but for all scientific research supported by the government. You might be surprised that the inspiration came from the Manhattan Project:

That geographic dispersal of research facilities was a brilliant decision made by Vannevar Bush, the president of the Carnegie Institution and later appointed by FDR to direct the Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II. In 1945 Bush published a report entitled “Science – The Endless Frontier” in which he outlined an ambitious path forward to ensure that the U.S. remained as the dominant science and technology power given what had just transpired with the Manhattan Project. A key feature of Bush’s recommendation was that the Federal government should invest heavily in basic and applied research by capitalizing on the infrastructure already present in our universities. That was clearly a success; for example, the Manhattan project leveraged the existence of cyclotrons at the University of Chicago and the University of Rochester to conduct research on plutonium – both its potential as a military device and its biological consequences for those exposed to its radiation.

Bush realized that to build dedicated research institutes from scratch would be hugely expensive and that a more cost-effective alternative would be to pay indirect costs to universities to leverage their already existing (or easily expanded) infrastructure. This also allowed biomedical research to be geographically dispersed throughout the country to allow for easy access to thousands of patients without transporting them to a single location. And to be clear, this university infrastructure is not just bricks and mortar. It is also the presence of scholarly information in libraries, the expertise of faculty unrelated to any given grant such as mathematicians and statisticians, computers and other shared items of equipment, and a highly educated workforce of faculty, staff, and students all of whom are already located in the same place. Other countries opted for a different model, such as France with their CNRS labs and Germany with their Max Planck institutes, which are not directly affiliated with a university. But it took them decades to catch up to the Bush model in the U.S.

So let’s be clear that indirect costs are not fluff. Moreover, they are negotiated with NIH (or the relevant Federal funding agency such as NSF, NASA, Department of Defense, etc) and, importantly, they are audited on a regular basis to make sure that the government is not being overcharged (e.g., as the mortgage on a building is paid off or utility rates go down). It should also be apparent that indirect costs differ by location – the cost of buildings, utilities, and administrative salaries is not the same in Palo Alto as in Iowa City.

Again, not to sound like a broken record (if people even remember what a broken record sounds like anymore), this is a very complicated issue and the current system has evolved over many decades going back to the 1940s. There are sound and understandable historical reasons why the government decided to fund science using a model in which it paid investigators at universities across the country to do the research, including indirect costs that the universities themselves required to provide the necessary infrastructure and staffing to do the research and administer the grants. And the system has been wildly successful, the claims of some of DOGE’s fans notwithstanding. There’s a reason why US biomedical research is the envy of the world.

Not that this administration seems to care. After all, to address the tradeoffs that would come from trying to cut F&A cost rates in order to shift money to the direct costs of more new grants requires an actual understanding of the system, knowledge of what F&A costs cover, and a study of potential downstream effects of the various solutions that have been proposed over the years. There is no evidence that I can find that either Elon Musk, DOGE, or anyone in the Trump administration has applied anything resembling through to this budget cut.

Think about it. It would be one thing if DOGE had announced that it would be applying the new F&A rate only to new grants awarded after February 10. That would have been difficult enough to deal with, but at least there would be some time for universities to adapt given that the new rate would only be applied to grants that they haven’t received yet. That’s not what happened. DOGE applied this cut immediately to existing grants as well, starting, well, today. That constitutes an immediate large budget cut to universities that do NIH-funded research, an immediate huge shortfall that few universities will be able to cover. (I know my university, which is a public university in an urban setting and that does not have a large endowment, is unlikely to be able to.) Even those with a large endowment might not be able to shift enough of the endowment over to covering expenses normally covered by F&A costs attached to their NIH grant portfolio, and there are a number of reasons why their administrations might not want to do that.

Likely outcomes include:

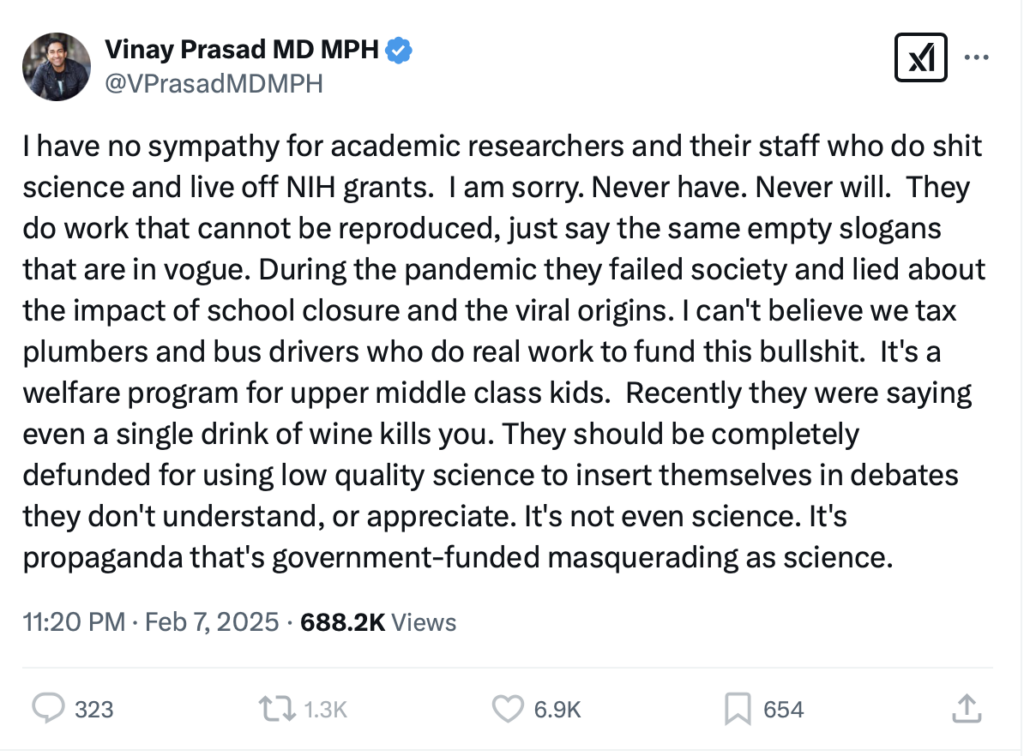

That point about administrative costs being so high because of the bureaucracy involved in submitting and administering NIH grants hits home. Dealing with regulatory issues, the paperwork involved in submitting grant applications and then yearly reports, as well as all the regulatory issues around animal facilities, clinical trials, and the like are very time-consuming and expensive. Some of that would be difficult to cut—for example, who wants to skimp on safety regulations for clinical trials and IRBs?—but a lot of it could be streamlined. As for gloating over good people, such as technicians, support staff, secretaries, and the like, losing their jobs as a result of this, which will happen, speaking of gloating, right on cue Dr. Vinay Prasad enters the picture:

I do love Dr. Prasad’s civility, don’t you?

Once again, I can’t help but wonder how much of Dr. Prasad’s hostility towards the NIH is due to his never having been funded by the NIH. Seriously, search NIH rePORTER for his name. He’s never been the principal investigator of an NIH grant, and it shows. One can’t help but wonder how much of his hostility towards the NIH is sour grapes. On I, on the other hand, have been the PI on an NIH R01. I also openly admit that my lack of success renewing the grant was probably more my fault than any fault of grant reviewing system at NIH. Attacking that which he hasn’t been able to successfully do is a pattern with him. For example, Dr. Prasad, as someone who’s never won NIH funding and attacks the NIH, likes to demand “RCTs” on everything, even though, as far as I can tell, he’s never designed or carried out an RCT on anything or even really thought about what the various RCTs of everything that he blithely calls for would actually entail, much less whether any of them would be ethical. (Hint: He doesn’t care; he proposes them whether they would be ethical or not, such as his “cluster RCTs” of the childhood vaccine schedule. It’s as if he is utterly ignorant of the term “clinical equipoise.”) In addition, it is important to note another thing. As we know from his blog posts, Dr. Prasad completed a fellowship at the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Clearly, something happened there that soured him on the NIH, a hostility that’s only grown since the pandemic hit, although damned if I can figure out what it was that triggered him as I read his rants.

Notice how Dr. Prasad has gone all-in on what the real motivation behind these cuts are: an attack on “DEI.” Indeed, he’s been rewarded, too, for his diving headfirst into culture war tropes:

Wow! Quoted in an email press release from the White House! Thirsty as he’s been for a position in the Trump administration, maybe Dr. Prasad has finally gotten the attention of someone who might give him what he clearly wants so very, very badly. As for his “defense” of this action, technically what he is saying is true, namely that the overall NIH budget hasn’t been cut, it’s a deceptive spin. Cutting indirects right now, with just a promise to move the money to funding new grants in the future will definitely be a massive budget cut now. Indeed, Dick Aslin, wag that he is, listed all the NIH Funding from the top ten states that voted for Donald Trump in 2024 and found that they have a combined total of $12.287 billion in NIH awards producing an economic impact of $31.7 billion:

This figure includes both direct and indirect costs, but a reasonable estimate of the cut in funding if the 15% rate is upheld is $1.5 Billion. Many of the public universities will be forced to terminate research grants because they cannot, especially in the short run, balance their budget by quickly raising state taxes by $1.5 billion. So the ripple effect will not only be layoffs of staff, reducing the more than 150,000 employees supported by these grants, but also how those employees spend their salaries to support the local economy – a significant drop from $31.7 Billion – and the loss in tax revenue from these salaries at the state and federal levels.

Let’s just put it this way. Not only would this immediate massive cut hobble biomedical research used to improve science-based medicine, but the economic impact will be potentially devastating. This is not how you solve a problem in a manner designed to strengthen the system, improve the rigor of scientific research funded by the NIH, and spread the pot of research money around to more investigators. It’s how you hobble the system for a generation, possibly even destroying it. Is it “political” to say that? Yes, but again, as I’ve argued many times, this blog has never been apolitical. Indeed, we’ve gone after liberals and Democrats a lot in the past; e.g., Sen. Tom Harkin, who in the 1990s foisted the scientific abomination that is the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health on the NIH. I’d even say that if Trump wanted to get rid of NCCIH, I’d be totally behind him on just this one issue. He won’t, though, given how much “wellness” grift has become a favorite among his supporters. Moreover, never before since I started paying attention to these issues has either party gone anywhere near as far as Trump has gone attacking federal science infrastructure. Seriously, back when I first started writing about RFK Jr. and the antivax movement was commonly viewed as more a left wing rather than a right wing phenomenon, never in a million years would I have envisioned him being nominated for HHS Secretary, much less being on the cusp of being confirmed for the post this week. (He will be confirmed by the way. Depressingly, that’s my prediction.)

Now let’s look at some reactions to this announcement.

Contrarians rejoice, spreading misinformation

Naturally, as I expected the moment I first read the NIH announcement, Dr. Vinay Prasad posted to his Substack an article defending the action. Like his attacks on NIH peer review and his calls for a “modified lottery” to distribute grants, it’s immediately clear that he hasn’t thought very deeply about this and is all about the rhetoric, not the policy, in NIH reduced indirects from 60+% to 15%: 10 things you should know. Let’s just say that these ten things range deceptive spins on the announcement to half truths to outright nonsense, for example #1:

The NIH is now in line with many philanthropic associations that cap indirects at 10-15%. See below. This is widely considered acceptable by universities.

I already dealt with that one above. The way the the rates are computed and negotiated by the NIH are not comparable with how private foundations compute and negotiate indirect rates. He should know this, being the recipient of Arnold Ventures (a private foundation that issues research grants) largesse. (One can see the methodolatry and fetishization of randomized controlled trials in one of its request for proposals, Strengthening Evidence: Evidence Support for RCTs to Evaluate Social Programs and Policies. Arnold Ventures, not coincidentally I believe, allows 15% indirect costs for university-based projects.)

Next up:

This will dramatically change academic incentives. Many universities have an unspoken rule that you cannot become associate or full professor without NIH funding. They claim that this rule exists because NIH funding means your work has passed the highest hurdle— acceptance by peers—but that was always a bad argument. If you publish papers, you have acceptance by peers. Instead, admin made this rule because it enriches them.

Funny, but Dr. Prasad became a full professor at UCSF without NIH funding. In fairness, he’s not entirely wrong about one thing. It’s definitely very difficult to become a full professor at a medical school without NIH funding. However, Dr. Prasad apparently managed it with just foundation funding—and funding from primarily just one foundation at that! To be honest, I’m still wondering how he pulled that one off. Personally, I don’t think it’s bad to incentivize obtaining NIH funding, given that NIH funding tends to require the most rigorous peer review compared to most foundations.

Next up, I cringed:

The university has become a bloated bureaucracy. Redundant admin, and excessive administrative hurdles to do research. Because money is fungible, this exists because of indirects. This will force universities to fire many unessential personnel. We need to make less paperwork to open trials. This might even improve research, as we strive for efficiency.

Dr. Prasad wouldn’t know “unessential personnel” if they bit him on the posterior. His is the sort of research that doesn’t really require much in the way of regulatory approval, given that what he does is mostly critiquing existing literature and clinical trials. He really appears to have little clue how much work it is to administer clinical trials and to do basic and animal research. Moreover, it’s impossible to “make less paperwork to open trials” without changes in regulation from Washington, DC. The reason that it takes so much paperwork to open a clinical trial is primarily due to those pesky human subjects protection regulations and animal welfare regulations, as well as health and safety regulations covering laboratories.

Next up, even more cringe:

Indirect costs are taxpayer money that vanishes. The NIH states, “Indirect costs are, by their very nature, “not readily assignable to the cost objectives specifically benefitted” and are therefore difficult for NIH to oversee.” We don’t know what they money is spent on, but, because money is fungible, indeed some of it is spent on things that Americas disagree with: mandatory DEI training classes and modules and other programs of this nature. Some of it is spent on alcohol at social events, business class international travel, and lavish retreats. That’s the nature of money. How do you justify taxing the plumber to pay for you to fly Business class to Singapore?

There you have it, the war on “woke” and “DEI.” As for alcohol at social gatherings? Geez, it’s difficult for us to offer alcoholic beverages at functions not funded by grants or indirects; our university has strict rules about that, and I bet that UCSF does too. As for business class travel, seriously? Travel to present at conferences is included as part of direct costs of NIH grants, not indirect costs. Seriously, you can budget travel into your grant to allow you to present at scientific or medical conferences. I honestly don’t know where Dr. Prasad got this one from, although I do applaud him for not using an example of traveling business class to China, the better to dogwhistle. That must have required some restraint on our part..

I mean, he basically repeats the same thing in a later bullet point (#7) claiming inefficiency in the use of F&A costs,, “joking” that the “NIH is spending 47 billion dollars for 5 grains of rice, and 2000 DEI training seminars.” (That’s a joke, but you get my point).” Truly, Dr. Prasad is turning into a one trick pony.

Here it gets interesting:

At first, I believed that the NIH should have made this change more slowly. Turned the indirects down year by year, but with a little more reflection, I think the shock and awe approach has some virtue. It will scare universities to immediately work to lower their administrative costs. If they turned it down slowly, changes may not occur.

Dr. Prasad should have stuck with his first instinct, which was far closer to correct than his current schtick. Shock and awe will likely do nothing more than cause a lot of good people to lose their jobs right now. Chaos and disruption are not a good recipe for improving our nation’s biomedical research, the better to improve science-based medicine with more effective treatments and better understanding of disease mechanisms. Once you wreck something, it’s really difficult to rebuild it at all, much less to rebuild it in a better form. On a related note, in #8 he suggests that 15% is merely a “starting point for debate” that could be “negotiated to 25% or something a little less immediately painful,” while blithely dismissing all the pain it will cause with a jaunty, “sometimes you have to open with a strong gambit.” I’m sure all the people who stand to lose their jobs if this rate is not increased back to something closer to what it was before will appreciate such negotiating tactics.

Next up, more misunderstanding:

Universities never took their NIH indirects and tried to make research reproducible. If universities, really cared about veritas, they could have used some of these funds to advance reproducibility— making sure published experiments are able to be replicated. If an experiment cannot be replicated, you did not learn anything true or enduring about the universe. Universities have not made substantive efforts to tackle this problem— which means, they largely don’t care about veritas. They are happy with the status quo. That’s why I said this:

Dr. Prasad sure is one angry dude, isn’t he? I wonder why he’s so full of fury, given that he’s got a cushy tenured professorship at UCSF—and without ever having to have obtained any NIH funding, at that!—lots of publications, lots of money coming in from his monetized Substacks, a huge megaphone to broadcast his contrarian message to lots of people, and now, it seems, the ear of the White House. Why does he feel so “persecuted”? Why does he nurse such anger and grievance? One also wonders: How reproducible is Dr. Prasad’s own research? (Sauce for the goose, as they say.) Inquiring minds want to know, they do, and Dr. Prasad never seems to show much concern about others reproducing his work, at least not anywhere as much as he does about NIH-funded research and research that he doesn’t like.

Sarcasm aside, this is all ust another nice-sounding but empty Prasad trope. How should universities take their indirects and make research reproducible? (As usual, Dr. Prasad doesn’t say.) Remember, that’s not the purpose of indirects, which go to support infrastructure needed for NIH research at a university. There has been a widespread effort going back years and years to make research more reproducible, but it doesn’t lend itself to easy soundbites of the sort Dr. Prasad makes. Let’s just put it this way. It wouldn’t be a bad idea for the NIH to devote more funding than it currently does to efforts to make scientific research more reproducible, but that’s not the function and purpose of F&A costs. Dr. Prasad knows that damned well, but he also knows that his audience doesn’t know it. Take from that observation what you will.

After saying that decreasing indirects might make researchers more accountable because universities don’t want to discipline researchers who bring in lots of NIH grants (a point that might or might not be true), Dr. Prasad continues:

Cutting indirects might even mean more science. Less money spent on the administration is more money to give out to actual scientists. I am shocked to see researchers crying about how much money the university gets— it means more grants can be given per cycle.

My response to this argument is simple: “Oh you sweet summer child. You really believe that the money saved is going to go to more research grants to more scientists?” Of course, that’s my response to people who make that argument sincerely, not to pundits like Dr. Prasad. It is, of course, theoretically true that the result of cutting indirects could be to redirect that money to more grants to more scientists or bigger grants to scientists. Given Trump (and Musk’s) history, though, does anyone really believe that this isn’t just a way to justify cutting the NIH budget next year? (I don’t.)

Indeed, one can look at a lot of this effort not so much as an effort to make the NIH more efficient by decreasing “bloated” indirects as payback. Because Anthony Fauci, Frances Collins, and the NIH funded research on COVID-19 and messaging about public health interventions during the pandemic that the Trump administration didn’t like, now Trump wants to make them pay. Because universities are perceived by Trump and DOGE as hotbeds of “DEI,” they want to make universities pay. I’ll give you an example:

So DOGE cut $168,000 budgeted to an exhibit in the NIH Museum about Anthony Fauci? That’s not even a rounding error in the NIH budget! It’s minuscule, but, boy, did they get back at Anthony Fauci by stopping the NIH from adding an exhibit on his career to the NIH Museum, even though Fauci headed NIAID for four decades.

That’s where Dr. Prasad is coming from, whether he actually believes what he’s saying or not or whether he is just saying what he needs to say to try to score an administration position. Personally I’m with Dick Aslin on one thing. If we are truly going to stick with this brain-dead one-size-fits-all hack-and-slash approach to indirect costs, then it should be applied to all federal grants, not just NIH grants:

But if President Trump and his new NIH Director, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who has not yet been confirmed, are determined to keep the indirect rate at 15%, surely we would be justified in asking that the same rate be applied to all government grants and contracts. This would include contracts to for-profit companies like SpaceX. I am not able to find (presumably proprietary) indirect cost rates for defense contracts (although a Rand Corp. study in 2000 confirmed they are higher than rates for universities), but I was able to find one example from a $404 million contract with Northrup-Grumman that spanned 7 years from 2019-2026. One of the differences between government grants (like those to non-profit universities) and contracts (like those to Northrup-Grumman) is that the salaries of the “key executives” who head up these contracts are included as part of indirect costs. The Northrup-Grumman contract listed the salary of their executive as $24 million. Even if this is spread out over 7 years, I can guarantee you that no university researcher is being paid $3.4 million per year by NIH. In fact, NIH has a salary cap of $221,900 per year. I look forward to the DOGE team reporting back to Congress about the indirect cost rate of SpaceX and the salary compensation Elon Musk is charging as part of NASA indirect costs.

As do I, but I suspect I will wait long. I also note that the salary cap described above is one reason why it’s difficult for universities to support clinician-scientists, who, thanks to their clinical activity, tend to command higher salaries than “pure” basic scientists. Any salary support for research that can’t be covered by an NIH grant due to the salary cap must therefore be covered by the university and/or from clinical revenue. Some universities can manage to do that to support clinical and translational research; many cannot.

In any case, I suspect that I will wait long for bootlickers like Dr. Prasad to be consistent in their calls for fiscal responsibility and go after where the real money is being spent on indirects. I realize there’s no way that’s ever going to happen.

The attack on the NIH and science-based medicine continues

The bottom line is that cutting indirects to 15% across-the-board is clearly not a well-thought-out policy. There is a policy discussion to be had on this topic, but that’s not what DOGE and its cheerleaders (like Dr. Prasad) are interested in. What they are more interested in is grievance, to punish universities and the NIH because of grievances, mostly imagined. I fear what the cost will be to biomedical research in the United States and to science-based medicine in general as a result of these slash-and-burn tactics. It almost makes me relieved that I’m probably only 5-8 years from retirement, but it also makes me sad for all the hard working support staff who will lose their jobs and all the smart and ambitious young students and investigators with whom I interact, whose career prospects look much less promising now. It makes me sadder for patients, who as a result of ideology, grievance, and a lack of understanding of the system necessary to institute reforms that would actually improve it, are going to suffer as a result.

When I first said, “Say goodbye to the greatest engine of biomedical research ever created,” I worried that my title might have been hyperbole. Now I fear that it wasn’t alarmist enough. Worse, RFK Jr. hasn’t even been confirmed yet, nor has Dr. Bhattacharya, and who knows what further “disruption” they’ll bring?