Wool garments provide a cozy home for the eggs of body lice, which spread the bacterium Borrelia recurrentis.Credit: Kathy deWitt/Alamy

A deadly infection that is spread by body lice might have emerged thousands of years ago thanks to a new fashion trend: wool.

Ancient genomes of the spiral-shaped bacterium Borrelia recurrentis — which causes a neglected disease called louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) — suggest that the pathogen diverged from a less deadly tick-transmitted infection around 5,000 years ago.

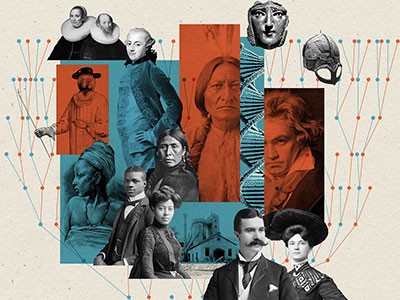

From Vikings to Beethoven: what your DNA says about your ancient relatives

This is not long after humans began domesticating sheep in the Middle East and around the time that wool textiles became common across Eurasia. Wool garments provide a cozy home for the eggs of body lice (Pediculus humanus), says Pooja Swali, a geneticist at University College London (UCL) who co-led the study, published1 on 22 May in Science.

Today, LBRF is found mostly in African countries including Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan and among people fleeing war, poverty and famine there — the disease thrives in overcrowded and disaster conditions.

Week-long fever

Records from classical Greece and Medieval Europe of days-long, recurring fevers characteristic of LBRF suggest that the disease might have been more common and widespread in the past. Antibiotics can now clear most B. recurrentis infections, but if they are left untreated, 10–40% of cases can be fatal.

As part of an effort to study ancient infections, Swali and her colleagues screened a large collection of ancient human genomes from Britain, looking for pathogens. They identified four B. recurrentis infections dating between 2,300 and 600 years ago.

Researchers extracted genomes from human remains in Britain to study ancient infections.Credit: Adelle Bricking

Further sequencing of the British strains and comparisons with one other ancient B. recurrentis genome sequence — from medieval Norway — and modern relatives indicated that the species diverged from its closest relative, the tick-borne Borrelia duttonii, between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago.

This time period overlaps with increasing use of animal products such as wool, milk by humans across Europe and Asia. “Things that you wouldn’t necessarily think of as creating the opportunity for new pathogens — like clothing technology, like wool — can provide the opportunity for these diseases to emerge,” says Pontus Skoglund, a palaeogeneticist at the Crick Institute in London, who co-led the study with Swali and evolutionary geneticist Lucy van Dorp at UCL.